Behind the Garden Gate

Rene Lynch and the Wilderness of Childhood by Eleanor Heartney

In an essay published recently in the New York Review of Books, novelist Michael Chabon ruminates on the magical – and increasingly endangered – “Wilderness of Childhood”. By this he means that geographic and psychic zone of freedom where children set off for uncharted territories and learn to test themselves without benefit of adult supervision. Lamenting the near disappearance of that zone under pressure from today’s overprotective parents, he suggests that it is a vital component of imagination, childhood development and art. He notes, “Childhood is, or has been, or ought to be, the great original adventure, a tale of privation, courage, constant vigilance, danger, and sometimes calamity. For the most part the young adventurer sets forth equipped only with the fragmentary map—marked here there be tygers and mean kid with air rifle—that he or she has been able to construct out of a patchwork of personal misfortune, bedtime reading, and the accumulated local lore of the neighborhood children.”

This Wilderness, shorn of familiar guideposts and full of unexpected personages and encounters, is also the subject of Rene Lynch’s lyrical paintings. But while Chabon, drawing on his own childhood, envisions it largely in male terms, Lynch gives us the female version. Her paintings are full of beautifully depicted young women on the cusp of puberty who seem to have slipped free for the moment of the deadening effects of civilization. They wander amid bowers of garlands, or scatterings of branches and leaves. They wear dresses that are vaguely contemporary, but there is little else to indicate the presence of the modern world. Whether traveling alone or in pairs, they frequently find themselves in the company of animals – cats, crows, falcons, even frogs - creatures who, as in mythology, legend and fairy tales, are at once symbols of various emotional states and sentient characters in their own right.

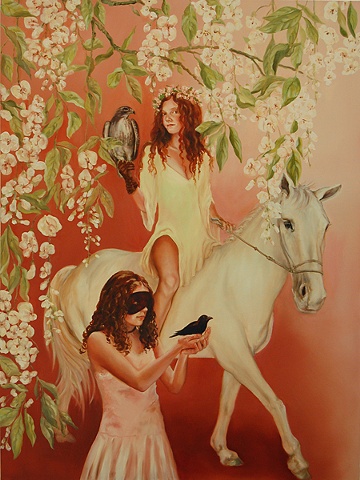

Procession presents two girls, similar enough in appearance to be sisters, emerging from an otherwise undefined space framed by a cascade of flowers. One sits astride a white horse holding a falcon, much in the manner of a medieval huntswoman, and casts an inquiring glance in our direction. The other wears a mask and is preoccupied with the crow in her hand. In Apples, two girls are accompanied by two crows. One stands on a stepladder, and, with echoes of Eve, reaches for an apple on the heavily laden branch above. The other, kneeling on the ground, holds a basket of apples to which she appears about to add another. In Golden Cages, there are three girls, two holding hands as they walk off in the distance. The third occupies the foreground and smiles as she turns her head toward the viewer, as if inviting us to follow. They each carry an empty birdcage from which the white doves fluttering about seem to have escaped.

Lynch creates her characters and her compositions using a variety of source materials, including photographs of young girls clipped from magazines and photographs taken by the artist of children of friends. These become the basis for composite portraits that nevertheless have a startling individuality. They are arranged in deliberately generalized natural settings – often involving a luminous void encircled by leaves, flowers or the branches of trees. They are painted with a careful attention to detail, with a mix of hyperrealism, fantasy and fidelity to natural detail that brings to mind the paintings of the Pre-Raphaelites. One is also reminded of the intermingled realms of nature and dream in Victorian fairy paintings, and the sinuous forms of classic children’s book illustrator Arthur Rackham. There is also something of the awkward grace and not yet conscious sexuality in the fine portraits of girls and young women by contemporary photographers like Renika Dykstra and Sally Mann.

The works have a powerful literary component as well. There are echoes of biblical tales – especially the prelapsarian idyll of Eve in the Garden of Eden – in works like Apples. Other works bring to mind the enchanted forests of Brothers Grimm, or medieval legends like the story of the Unicorn who could only be tamed by the purest of maidens, a reference particularly potent in a work like Procession.

There are also more contemporary references. One senses a kinship to all sorts of contemporary epics, ostensibly for children, which involve coming of age stories couched in the language of quest, ordeal and trial. From Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland to the narratives of writers like Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, and of course, J. K. Rowling, such epics draw on myth and legend to present allegories of the difficult passage from childhood to adulthood. In the process they offer a counter strain to the skeptical and rationalizing tendencies of modernism. Of these contemporary bildungsromans, the closest in feeling to Lynch is Philip Pullman’s Miltonesque trilogy, His Dark Materials. Unlike many of the other stories, Pullman’s primary character is a young girl – Lyra Belacqua - who must pass through many ordeals and many parallel universes before she discovers her own nature and saves the worlds from the oppression of evil. One of Pullman’s most remarkable inventions in this tale is the daemon, a kind of animal familiar who is attached to each individual and is actually an external manifestation of his or her soul. One’s daemon is literally a part of oneself, sharing a kind of communication sometimes experienced by identical twins, and can only be severed at risk of actual or psychic death.

This show includes a set of drawings and lithographs which present solitary young women clasping an animal. The animals, which include crows, frogs, cats and rabbits, nestle in their arms without any sign of conflict or struggle. Their connection is so tender and so essential, it is hard not to think of Pullman’s daemons, though that is not their inspiration. But what both Pullman and Lynch have captured is the kind of Wordsworthian link to nature that often overwhelms young girls at this stage of their life.

The delicacy of these works evokes a moment in the lives of young women when they stand poised between innocence and experience. It is a place which they must enter without adult supervision and which they emerge from better equipped to face the conflicts and challenges of adulthood. In these beautiful paintings and drawings, Lynch captures the strangeness and the beauty of the female experience of the Wilderness of Chlldhood.